4 Things Most Tech Folks With ISOs Don’t Know About AMT (It's Likely Not As Bad As You Fear)

Pre-Read: Key Questions This Article Answers

ISOs and AMT can be incredibly confusing. But for many, the impact is not as bad as they fear. In this article we dive into the top-4 AMT items most tech professionals don't know (or fully grasp):

AMT is a Parallel Tax System

The AMT Tax Calculation Includes a Large Exemption ($88k - $137k)

AMT is a "prepayment tax"; if you pay AMT you get a CREDIT that can be recouped in the future

Selling ISOs frequently results in recouping a large part of your AMT credit

One of the more common questions we hear at 30-40 Wealth from clients is "will I need to pay AMT tax on this?"

Federal Alternative Minimum Tax (”AMT”), and some similar state tax systems (e.g. California’s Tentative Minimum Tax (”TMT”), can definitely be complex and difficult to understand, but in my experience, they are also frequently misunderstood and (many times) unjustifiably feared as a result.

Unfortunately, when it comes to AMT and stock comp, I’ve witnessed many individuals’ lack of understanding (or fear) of AMT result in suboptimal, or downright poor, financial decision making. For example, in the last few years I’ve encountered all of the following situations when an individual initially discussed their stock comp holdings and historical decisions:

An individual did not realize that paying AMT creates a credit that can be refunded to them in future years, and their DIY tax software didn't capture + adjust for the credit in future years, resulting in them missing out on more than $25,000

An individual had the choice of receiving either NSOs or ISOs (same strike price) and opted for NSOs because they “didn't want to have to deal with AMT tax”. But in actuality, their planned strategy for the options would not have triggered AMT and the ISOs would have provided them with materially more cash after-tax

An early employee (seed-stage) desired to exercise their ISOs in their first 1-2 years (the company was doing very well), but opted not to in order to “avoid AMT”. However, if they had exercised then, the AMT bill would have been very small (sub-$5k) + 100% recouped the following year. Instead, years later when they did exercise, they opted for/desired to conduct a disqualifying disposition of their ISOs, resulting in more than $100,000 of incremental taxes vs if they’d exercised years earlier

I completely sympathize with these individuals; the US tax code is unnecessarily complex (to say the least) — but these conversations also had many common threads. Synthesizing the hundreds of conversations I've had with tech professionals on this topic, I've found that there are frequently 4 key things about AMT that most individuals don’t know or fully understand. And once they do, their dislike (or fear) of AMT is notably reduced.

(1) AMT is a Parallel Tax System

When discussing AMT, most individuals are surprised to learn that their taxes are calculated two ways every year: (i) Traditional/Standard, and (ii) AMT. This is how AMT works; it’s a parallel tax system. Functionally, what happens each year is:

Your tax preparation software or your accountant input all of your tax details

The system follows the tax rules to calculate both standard and AMT taxes due

Standard and AMT are compared against one another — and you pay the larger of the two

Most individuals aren’t aware that this is occurring because (i) it’s largely done in the background by their software or accountant, and (ii) their standard tax calculation is frequently the higher of the two and what they owe. Where this sometimes changes for technology professionals is when ISO stock options are exercised. To understand why that is, it helps to dig in a bit more into the key parts of how AMT and standard taxes are calculated (2025):

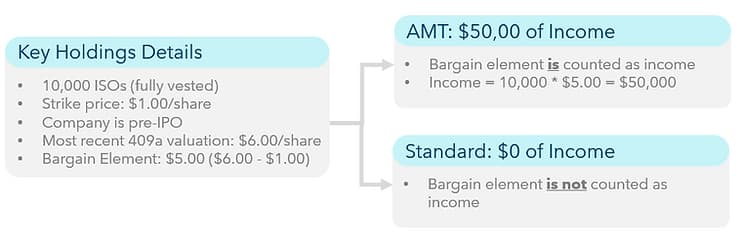

AMT. Simple 2-step graduated tax bracket of 26% up to around $230k; 28% above that. You get a large exemption (Single = ~$86k; married joint = ~$133k). The ISO bargain element is counted as income

Standard income tax. More complex 7-step graduated tax bracket (10% to 37%). ISO bargain element is not counted as income

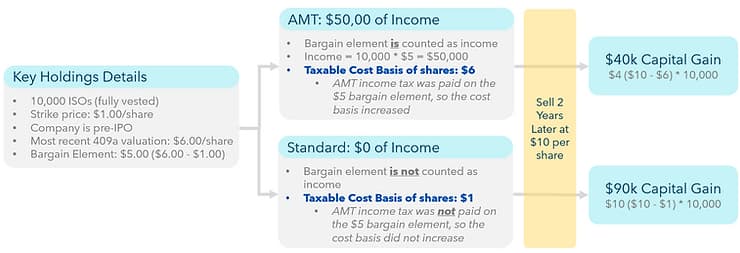

For tech workers with ISOs: the catch is how ISO exercise "income" is treated differently. As a quick reminder, the "bargain element" is the difference in price between (i) the company fair market value ("FMV") on the date of exercise and (ii) the option strike price. For example, an individual with 10,000 ISO options with a $1.00 strike price, and the company has a $6.00 FMV would generate $0 of Standard Income, but $50,000 of AMT income upon exercise:

(2) The AMT Tax Calculation Includes a Large Exemption ($88k - $137k)

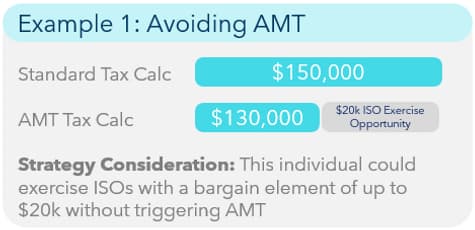

The AMT tax code was updated in 2018, resulting in a much smaller portion of tax filers now triggering AMT. A large reason for that is that the exemption taxpayers get when AMT is calculated was significantly increased. As of 2025, single filers have an exemption of $88,100 and married couples filing jointly get an exemption of $137,000.

What this means for tech workers: you may be able to exercise some ISOs in a tax year without triggering AMT. In fact, working with an advisor to run tax forecasts to determine how much you can exercise without triggering AMT is a commonly used tax strategy:

(3) AMT is a "prepayment tax"; if you pay AMT you get a CREDIT that can be recouped in the future

Unlike nearly every tax you pay (i.e. paid to the government and gone forever), AMT works differently. In most cases I encourage individuals to think of the incremental tax they pay due to AMT as largely a prepayment of future taxes (I'll avoid a philosophical debate of how silly or annoying that is; it's just how it works).

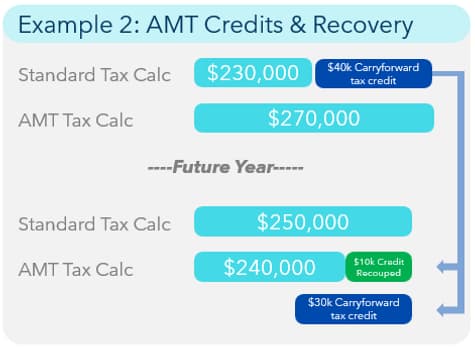

Details: As noted above, AMT and Standard taxes are calculated each year and you pay the higher of the two. Tech workers with ISOs commonly pay AMT in a year or two due to large ISO exercises, but then revert back to "normal" and pay Standard taxes in future years. If this occurs, you'll likely be able to recoup a large portion (or all) of the AMT excess tax you paid over time. How much AMT credit you can recoup each year is largely the inverse calculation of determining if you owe AMT. I've found it's easiest to illustrate this in an example:

Paying AMT tax: When your AMT tax calculation (e.g. $270k) is more than the Standard calculation (e.g. $230k):

You pay the higher ($270k)

You create an AMT credit with the IRS for the excess ($40k in this example: $270k - $230k)

Recouping AMT Credits: When your Standard tax calculation (e.g. $250k) is more than your AMT calculation (e.g. $240k) and you have an AMT credit from a prior year:

Your owed tax bill is the higher of the two ($250k)

You recoup some of the AMT credit; specifically the difference between the two calculations ($10k in this example: $250k - $240k)

This results in the net amount of cash you pay for tax is $240k ($250k - $10k)

Last, some of the AMT credit remains ($30k in this example; $40k - $10k), so it carries forward into future years

(4) Selling ISOs frequently results in recouping a large part of your AMT credit

As noted above, most individuals' Standard tax bill is higher than their AMT calculation due to the large AMT exemption. That said, even with the large exemption, the different calculation for AMT (what is included/excluded in AMT vs. Standard) frequently results in the final tax calc for each differing by less than $20k (e.g. $100k standard tax vs. $85k AMT). So, if you have an AMT credit under $100k, you'd likely recoup most (or all) of it in a handful of years. It'd be annoying to have to wait that long, but you could reasonably expect to get most/all of it all back in time.

But what if you have a large AMT credit due to a large ISO exercise: $200k, $500k, maybe even more than $1 million? It can/does happen, and in these cases, individuals would rightfully be concerned that any tax benefit from an ISOs would be lost (or worse, become a detriment) due to paying AMT tax and having an AMT credit that they could not recoup in their lifetime. Fortunately, this is not usually the case because the reported cost basis of an exercised ISO is different for Standard and AMT taxes:

If you've paid income tax on the bargain element of an ISO (e.g. AMT tax calc), the cost basis on those shares is increased.

If you haven't paid it (e.g. Standard tax calc), your cost basis didn't change.

When you sell the shares, the amount of capital gains in Standard vs. AMT calculations will be substantially different as well.

Key Takeaway: Selling ISOs (qualified disposition) frequently helps individuals recoup a large portion of AMT credit. In the example below, an individual who paid nearly $600k in incremental tax due to AMT would recoup more than 70% of that back in the year they sold the ISOs. Additionally, the remaining unrecouped portion would continue to roll forward and be available for incremental recoupment in future years.

Additional Considerations: Tax Optimization

Beyond the 4 key items detailed above, there are additional tax intricacies, optimizations, and strategies that could apply -- but which are outside the scope of this blog post. While not detailed in full (they'll be covered in a separate, future post), they're listed below to help individuals ensure they consider all aspects specific to their situation:

Consider and optimize for state taxes, especially if your state has AMT tax

Consider and optimize for unique AMT tax treatment if the ISO qualifying disposition creates an AMT capital loss

Consider exercising ISOs in January or February to gain additional benefits and/or flexibility

If you have multiple stock tax lots, strategically select which lot(s) to sell first/last to lower your tax bill

Ensure that certain positions meet holding-time requirements to achieve preferential tax treatment (e.g. ISOs qualifying disposition, Qualified Small Business Stock, long-term-capital-gains treatment)

Pair capital gains from sales with harvested tax losses and/or opportunity zone investments

Carve out shares that one intends to donate (and realize double or triple tax benefits from doing so)

How to appropriately consider ISOs as part of your stock comp selling plan

Consider and adjust for any anticipated changes in future tax brackets (e.g. state relocation, sabbatical, early retirement)

Article Last Updated: May 27, 2025